Pinkwasing is etymologically a borrowing of the words pink and washing. The Breast Cancer Association coined the term as a criticism of fast food chains and multinationals that campaigned for a cure for breast cancer while maintaining corporate practices harmful to public health. The LGBT community later adopted this term, focusing on the false image of progress of brands that carry out marketing actions in support of the cause (Llanos, 2019).

Pinkwashing began to become popular in a context in which, in the mid-1990s in countries such as Spain, the LGTB collective’s protest actions began to become increasingly consolidated, with a specific day being proclaimed for holding a demonstration and a rainbow flag being displayed for the first time as a symbol of identity for the whole community.

In the specific case of Madrid and parallel to the demonstration model that developed in the mid-1990s, a process began that would culminate at the beginning of the new millennium: the transformation of “gay” into a profitable brand. Gaypitalism is the term used by LGBT activist Shangay Lily to explain how entrepreneurs got rid of LGBT culture and folklore to transform it into a stereotypical product:

“The 1990s began with a blatant appropriation and massification of gay culture by the capitalist machine, stripping it of its essence and commodifying it for mass consumption in its most folkloric and colourful aspects” (Lily, 2016).

Thanks to the resounding success of drag queens venues, such as the pioneering Shangay Tea Dance, aspiring entrepreneurs saw the opportunity to make the neighborhood of Chueca (Madrid, Spain) the nerve centre of LGTB business, the clearest example being Librería Berkana, becoming a showcase for the declaration of pride in the struggle, which would eventually be joined by cafés, restaurants, travel agencies, laundries, publishing houses and countless other businesses. Later this neighbourhood was perceived as a niche market and an opportunity to open businesses dedicated to the LGBT community, but lacking in discourse and advocacy.

“With these entrepreneurs, the gay brand began to be manufactured, falsifying the sense of community building in order to introduce heterosexist classism. The industry ended up dictating the identity of the collective and began to reproduce in it the same system that had marginalised, crushed and categorised it” (Lily, 2016).

Brands then chose the image of the middle-aged, white, masculine, handsome, educated, sensitive, wealthy, childless, integrated and healthy gay man as the only valid representation. Diversity became invisible the day exclusivity, status, wealth and normativity became synonymous with gay.

The LGBT community ceased to be a social community and became a market sector. Is this really a problem? From the point of view of social struggle, yes, because there would be a risk that those big companies that dye their logo with the rainbow flag would empty the real meaning of the demonstration with pinkwashing to turn it into a product.

The problem with the brands that occupy the spaces of the LGBT Pride event is that they leave no room for the issues that are really important for the community. Brands and the companies behind them must understand the situation of the community and take the necessary measures for their inclusion and normalisation, both in the workplace and in their advertising.

A clear example of bad practice in relation to the collective is El Corte Inglés, which has been taking advantage of the showcase that is the LGTB Pride since 2014 when AEGAL allowed it to be a sponsor, when in fact the rest of the year it has books in its catalogue such as “How to prevent homosexuality” by Joseph Nicolosi. This makes El Corte Inglés an opportunistic and very inconsistent brand that is only interested in profitability and understands the collective as a mere product. This is the clearest example of bad practice.

How to recognise a pinkwashing campaign?

- It is only active during the month dedicated to LGBT Pride (June).

- They do not collaborate with or donate profits to any LGBT cause.

- It does not participate in the LGTB struggle outside the month of June.

- Low or no diversity representation

- Does not participate in social causes

- Uses problematic slogans such as “Love wins”.

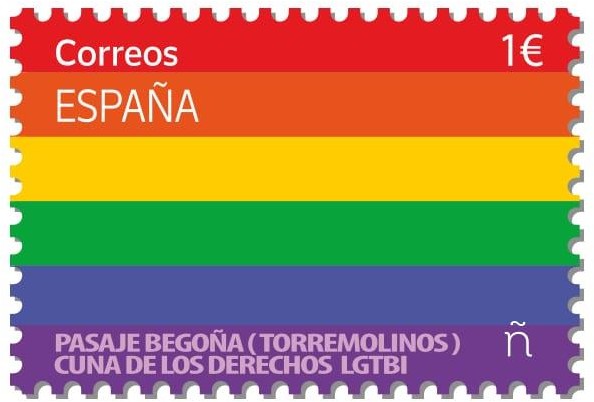

In contrast to the bad practices in the specific case of El Corte Inglés, an example of inclusive advertising and, moreover, successful in terms of profits, is the Correos (Post Office) campaign presented in June 2020. Correos showed a campaign that was in line with its rebranding strategy in favour of social causes, as Ana Salazar, political consultant and advisor to the Junta de Andalucía, pointed out in an interview in the Huffington Post newspaper: “Correos is a public company that is well valued, but when the competition arrives, it has to differentiate itself and it does so by embracing social causes. It is about the company providing not only a service, but also added value” (Loren, 2020).

How to recognise a campaign that does not engage in pinkwashing?

- It is active all year round

- They donate part of the proceeds to an LGBT association or collaborate with them

- It does not use slogans or representations that are not inclusive.

- Diversity representation is high, not only targeting cisgay men

- The brand or company is positioned in favour of various social causes

- Advertiser has an action plan against discrimination in the workplace

In conclusion, the occupation of LGBT Pride spaces by brands is corrupting the essence of the Pride movement.

Based on the initial assumption was that the issue of the commodification of LGBT Pride and the excessive branding of the event was corrupting the essence of the origins of the LGBT rights demonstration, there is an opens a debate on how LGBT representation in advertising is.

LGBT people demand inclusive and diverse advertising, but above all they demand equal opportunities and equal treatment. No matter how much a company may have advertising actions that support the collective, if there is no egalitarian space and a labour commitment that acts in favour of rights and equal opportunities, the company will not be providing optimal and real support.

References:

ÁLVAREZ, Rober (2020): “El Orgullo de Correos: el coste de la campaña LGTBI ha supuesto 10.351 euros”, Newtral, en: https://www.newtral.es/correos-orgullo-bandera-lgtb-coste-campana/20200624/.

HUDSON, David (2018): “Might this become the new Pride flag?”,Gaystarnews, en https://www.gaystarnews.com/article/daniel-quasar-pride-flag/#gs.DkFe3IY.

LILY, Shangay (2016): Adiós, Chueca. Memorias del gaypitalismo: la creación de la marca gay. Madrid, Ediciones Akal.

LLANOS MARTÍNEZ, Héctor (2019): “’Pinkwashing’, el lavado de cara a costa del colectivo LGTBI+ del que se acusa a Rivera”, Verne, en: https://verne.elpais.com/verne/2019/02/11/articulo/1549879220_602561.html.

LOREN, Eduardo (2020): “La campaña LGTBI de Correos, todo un éxito: costó unos 10.000 euros y ya lo ha recuperado con creces”, Huffington Post, en: https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/la-campana-de-correos-que-ha-desbordado-todas-las-expectativas_es_5ef09360c5b627efb396838b. [Fecha de consulta: 22 de enero de 2021]

MARTÍNEZ, Ramón (2017): Lo nuestro sí que es mundial. Unaintroducción a la historia del movimiento LGTB en España. Barcelona, Editorial Egales.

RODRIGUEZ-PINA, Gloria (2016): “Hazte Oír celebra la retirada del anuncio con gais de El Corte Inglés, pero la compañía alega otros motivos”, Verne, en: 35

https://verne.elpais.com/verne/2016/10/03/articulo/1475481437_124615.html.